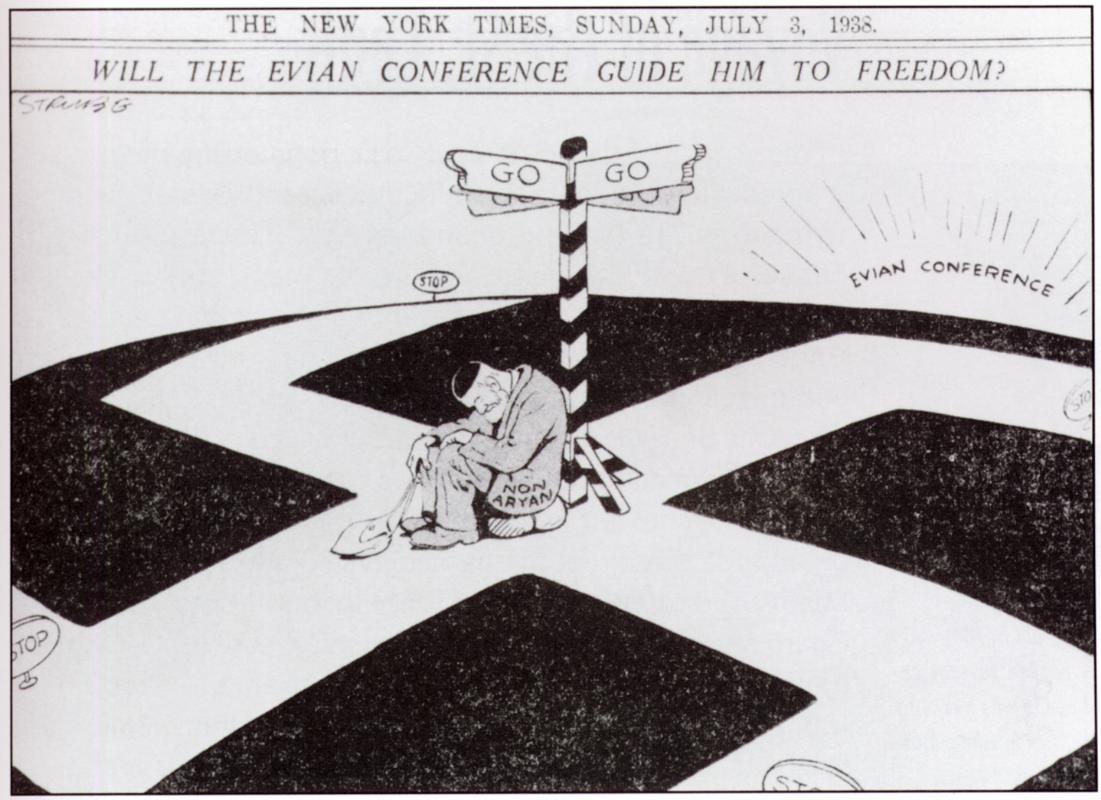

The plight of Austria’s Jews in the aftermath of the Anschluss generated pressure from some Members of Congress and journalists for U.S. intervention. State Department officials decided to “get out in front and attempt to guide” the pressure before it got out of hand. On March 24,1938, President Franklin Roosevelt announced that the United States was inviting thirty-three countries to send representatives to a conference on the refugee problem, to be held in the French resort town of Evian-les-Bains. All of those invited, except Italy, agreed to send delegates.

FDR emphasized in his announcement that “no nation would be expected or asked to receive a greater number of emigrants than is permitted by its existing legislation.” In addition, the Roosevelt administration privately promised Great Britain that Mandatory Palestine would not be discussed as a possible refuge. These conditions greatly reduced the possibility that the Evian conference would produce meaningful results.

Assistant Secretary of State George Messersmith bluntly told a private meeting of refugee advocates, shortly before the conference, that the delegates to Evian were likely “to render lip service to the idea of aiding the refugees accompanied by an unwillingness, however, to do anything to ease existing restrictions on the admission of immigrants.”

The conference opened at the Hotel Royal on July 6. Although the delegates all arrived on time, some of the early sessions were sparsely attended. The hotel’s chief concierge later recalled why: “All the delegates had a nice time. They took pleasure cruises on the lake. They gambled at night at the casino. They took mineral baths and massages at the Etablissement Thermal. Some of them took the excursion to Chamonix to go summer skiing. Some went riding; we have, you know, some of the finest stables in France. But, of course, it is difficult to sit indoors hearing speeches when all the pleasures that Evian offers are outside.”

The proceedings of the conference confirmed the skeptics’ fears. One speaker after another reaffirmed their countries’ unwillingness to accept more Jews. Typical was the Australian delegate, who bluntly asserted that “as we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one.” The only exception was the tiny Dominican Republic, which declared it would accept as many as 100,000 Jewish refugees, although that project never materialized, because the Roosevelt administration feared the arrival of so many refugees in the nearby Caribbean would enable some of them to sneak into the United States.

Newsweek, noting the appeal by the chairman of the U.S. delegation to the attendees “to act promptly” in addressing the refugee problem, noted: “Most governments represented acted promptly by slamming their doors against Jewish refugees.” Time, for its part, reported that Evian was the source of “still and unexciting table water [and] after a week of many warm words of idealism [and] few practical suggestions,” the conference “took on some of the same characteristics.”

Golda Meir, who later became prime minister of Israel, attended Evian as an observer. She concluded that “nothing was accomplished at Evian except phraseology.” At a press conference after the gathering, she remarked, “There is only one thing I hope to see before I die, and that is that my people should not need expressions of sympathy any more.” Another critic pointed out that “Evian” was “Naive” spelled backwards. The problem, however, was not naiveté so much as it was calculated indifference.

In 1979, the United States spearheaded an international conference at Lake Geneva, near Evian, on the plight of hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing the Communist victory in Southeast Asia. In an emotional keynote speech, Vice President Walter Mondale compared the gathering to the Evian conference, which he said “failed the test of civilization.” Mondale pleaded with the delegates to join the U.S. in rescuing the Asian ‘boat people’. “History will not forgive us if we fail,” he concluded. “History will not forget us if we succeed.” The speech is widely credited with inspiring many countries to take part in the rescue of those refugees. “The nations stepped up to the crisis,” Mondale’s chief speechwriter, Martin Kaplan, later recalled. “It was one of those rare occasions when words may actually have saved lives.”

Sources: Wyman, Paper Walls, pp.43-51;

Feingold, The Politics of Rescue, pp.22-36.