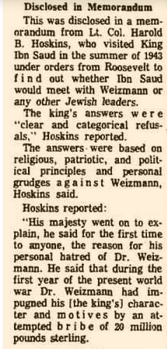

In late 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a Beirut-born U.S. army officer, Lt. Col. Harold Hoskins, to the Middle East to canvass Arab opinion. Hoskins’s final report to the president, the following spring, predicted that “world-wide [Zionist] propaganda” and “Arab fear of American support for political Zionism with its proposed Jewish State and Jewish Army” would cause Jewish-Arab violence in Palestine and an Arab uprising against Allied forces in the region. Hoskins urged the Allies to issue a statement declaring that all “public discussions and activities of a political nature relating to Palestine” were endangering “the war effort”and should “cease.”

One of Hoskins’s strongest supporters was Major-General George V. Strong, head of the War Department’s G-2 intelligence division. Strong claimed that any perceived U.S. support for Jewish statehood, for letting Jews enter Palestine, or even for temporarily housing European Jewish refugees in North Africa, would cause a Muslim “Holy War” that would “result in the death and destruction of several hundred thousand American soldiers.”

These arguments persuaded President Roosevelt, who jotted “OK – FDR” on the Hoskins proposal for an Allied decree banning public discussion of Palestine for the duration of the war. The British, too, embraced the Hoskins plan, and a date –July 27, 1943– was chosen for release of the joint Anglo-American declaration. Jewish leaders were shocked and furious to learn of the impending decree. Even Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, a Roosevelt loyalist, confided to a friend that FDR “seems to me to be completely and hopelessly under the domination of the English Foreign Office.”

Several of the president’s Jewish aides, although not sympathetic to Zionism, opposed the declaration because they feared Zionist activists would ignore the Anglo-American decree and thus stir up antisemitism by making Jews appear unpatriotic. Leaks to the media opened the door to criticism from Capitol Hill. U.S.Congressman Emanuel Celler charged on the floor of the House that “the joint statement will, with its ‘Silence, please’ drown the clamor of the tortured Nazi victims pleading for a haven of refuge.” In the face of this and other criticism, Roosevelt decided that plan was too controversial, and dropped it. However, the concept behind the plan, that Jews settling in the Holy Land would cause Arab attacks on GIs in the Mideast, remained fixed in the thinking of the Allied leadership. Throughout the Holocaust, the Churchill government, with the Roosevelt administration’s support, kept the doors to the Holy Land shut to all but a trickle of Jewish refugees.

Sources: Penkower, The Holocaust and Israel Reborn, pp.145-176;

Feingold, The Politics of Rescue, pp.216-217.