“The Bergson Group” was the name often used to refer to a series of political action committees in the United States during the 1940s that were headed by Hillel Kook, using the name Peter Bergson.

The nucleus of the group came out of the Irgun Zvai Leumi, the Palestine Jewish underground militia associated with Revisionist Zionist leader Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky. In 1937, the Irgun sent a number of its most promising activists to Europe to organize unauthorized Jewish immigration (aliyah bet) to Palestine. Chief among them were Kook, Yitshaq Ben-Ami, Alex Rafaeli, and Jabotinsky’s son, Eri. During the three years to follow, they succeeded in bringing an estimated twenty thousand refugees to Palestine, in defiance of British immigration restrictions.

As the clouds of war gathered over Europe, both Jabotinsky and the Irgun High Command increasingly came to believe that Washington would replace London as the center of the political struggles that would determine the fate of Palestine. For that reason, the Irgun in 1939 dispatched Ben-Ami to the United States to seek political and financial support for aliyah bet. He established an organization called American Friends of a Jewish Palestine (AFJP), with a small office in New York City.

THE RIGHT TO FIGHT

When the outbreak of World War Two made further aliyah bet transports almost impossible, Jabotinsky traveled to the United States in1 940 and launched a campaign for the creation of a Jewish army to fight alongside the Allies against the Nazis. Kook, Rafaeli, Eri Jabotinsky, and Samuel Merlin joined him in the U.S. and helped organize Jewish army rallies in the spring and summer of 1940. After Jabotinsky’s death in August, Kook and his comrades established the Committee for a Jewish Army of Stateless and Palestinian Jews. Kook, a dynamic public speaker, became its leader. He used the pseudonym Peter Bergson to shield his family in Palestine, including his uncle, Chief Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Kook, from the glare of public controversy.

The committee employed tactics that were unorthodox for that era, including mass rallies, lobbying Congress, and full-page newspaper ads with headlines such as “Jews Fight for the Right to Fight.” Many of the ads were authored by the Academy Award-winning Hollywood screenwriter Ben Hecht. The ads featured long lists of political figures, labor leaders, intellectuals and entertainers endorsing the Jewish army cause. Some of the ads were illustrated by the famous artist Arthur Szyk, a Bergson supporter.

The British government opposed the Jewish army proposal on the grounds that it might anger the Arab world. British and American sensitivity to Arab opinion was honed by their desire for access to Arab oil and their hope of keeping the Arabs from actively supporting the Nazi war effort. The British also feared that the existence of a Jewish army would intensify the pressure for establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Nevertheless, the Bergson Group’s public pressure campaign, together with behind-the-scenes lobbying by Zionist leaders, eventually persuaded the British to establish a Jewish Brigade. The 5,000-man force, assembled in late 1944, fought with distinction against the Germans in the waning months of the war, and Brigade veterans later helped smuggle Holocaust survivors to Palestine. Some also joined the ranks of the nascent Israeli army and took part in the 1948 War of Independence.

THE RESCUE CAMPAIGN

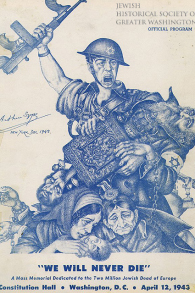

When news of the mass murder of European Jewry was verified by the Allies in December 1942, the Bergson Group set aside the Jewish army campaign and focused on urging the . Roosevelt administration to rescue Jewish refugees. U.S. officials contended, however, that rescue was impossible because of war conditions and major newspapers buried the reports of the killings in the back pages. To raise public awareness, the Bergson Group sponsored a Ben Hecht-authored dramatic pageant called We Will Never Die.

Hecht recruited the Hollywood elite for the project: Moss Hart as director, Billy Rose as producer, an original score by Kurt Weill, and starring roles for Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni, among others. We Will Never Die played to audiences of more than 40,000 in two shows at Madison Square Garden in March 1943. It was subsequently performed in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Washington, D.C.’s Constitution Hall, where the audience included First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, as well Supreme Court justices, Members of Congress, and foreign diplomats. Mrs. Roosevelt devoted part of her next syndicated column to the pageant and the plight of Europe’s Jews. For millions of American newspaper readers, it was the first time they heard about the Nazi mass murders.

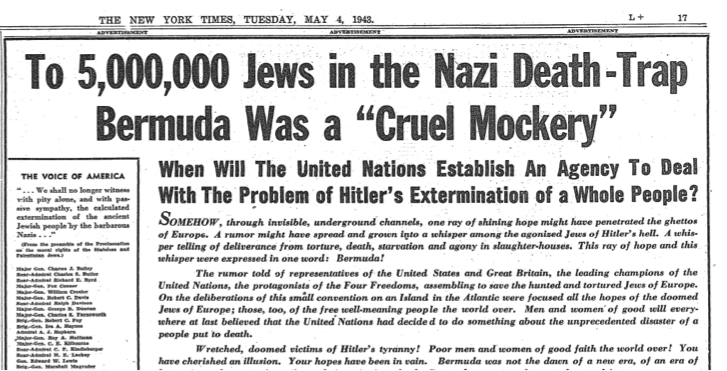

To head off mounting public criticism of the Allies’ abandonment of European Jewry, the American and British governments announced that their representatives would meet in Bermuda, in late April and early May, to discuss the Jewish refugee problem. Despite twelve days of discussions, the conference produced no concrete plans for rescue. The Bergson Group responded with a large advertisement in the New York Times, headlined “To 5,000,000 Jews in the Nazi Death-Trap, Bermuda Was a Cruel Mockery.” Many mainstream Jewish leaders likewise blasted the conference. Dr. Israel Goldstein, president of the Synagogue Council of America, said it was “not only a failure, but a mockery,” and bluntly added that “the victims are not being rescued because the democracies do not want them.”

As a retort to Bermuda, the Bergsonites organized a five-day Emergency Conference to Save the Jewish People of Europe, in New York City in July 1943. More than 1500 delegates participated, with panels of experts outlining ways to save Jews from Hitler. The conference received widespread coverage in the national press and on radio and gave important momentum to the argument that rescue was possible.

The fact that the chairs, speakers, and endorsers of the conference represented a broad range of prominent political and cultural figures from across the spectrum, including former president Herbert Hoover and Roosevelt cabinet member Harold Ickes, demonstrated the emergence of a bipartisan coalition for rescue.

THE RESCUE BATTLE MOVES TO CAPITOL HILL

The emergency conference concluded by transforming itself into the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe, and launched a campaign urging the president to establish a new government agency to rescue Jewish refugees.

During 1943-1944, the Bergsonites placed more than two hundred advertisements in newspapers around the country, with headlines such as “How Well Are You Sleeping? Is There Something You Could Have Done to Save Millions of Innocent People from Torture and Death?” and “Time Races Death: What Are We Waiting For?” The ads attracted significant attention. On one occasion, the First Lady told Bergson that President Roosevelt complained that one of the ads was “hitting below the belt.” Bergson replied that he was “very happy to hear that he is reading it and that it affects him.”

The ads and other Emergency Committee communications bore the names of a remarkable array of political, cultural and intellectual figures, among them the actress and acting coach Stella Adler; conductor Erwin Piscator; Chinese nationalist scholar Dr. Lu Yi-Ying; artist Arthur Szyk; the governors of Pennsylvania (Edward Martin, Republican) and Rhode Island (J. Howard McGrath, Democrat); Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Sigrid Undset; sculptor Jo Davidson; Congressman Samuel Dickstein (Democrat of New York); science fiction author Fletcher Pratt; and Rabbis Eliezer Silver (Orthodox) and Philip Bookstaber (Reform).

On October 6, 1943, three days before Yom Kippur, the Bergson Group, working with an Orthodox rescue committee call the Va’ad ha-Hatzala, organized a march by four hundred rabbis to the White House. It was the only rally for rescue held in the nation’s capitol during the Holocaust period.

Marching first to the Capitol, the rabbis were met by Vice President Henry Wallace and Members of Congress. Two of the protesters read aloud a petition urging President Roosevelt to create a rescue agency. They proceeded to the Lincoln Memorial, where they offered prayers for the welfare of the president, America’s soldiers abroad, and the Jews in Hitler Europe, and then sang the national anthem. Then they marched to the gates of the White House, where they expected a small delegation would be granted a meeting with President Roosevelt. Instead they were informed by a staff member that the president was unavailable “because of the pressure of other business.” In fact, the president had nothing on his schedule that afternoon, but had been urged to avoid the rabbis by his speechwriter Samuel Rosenman, who was embarrassed by the rabbis and feared the march might provoke antisemitism. Roosevelt decided to leave the White House through a rear exit.

Media coverage of the episode reflected, for the first time, a sense that American Jewry was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the administration’s refugee policy. “Rabbis Report ‘Cold Welcome’ at the White House,” declared the headline of a report in the Washington Times-Herald. A columnist for one Jewish newspaper angrily asked: “Would a similar delegation of 500 Catholic priests have been thus treated?” The editors of another Jewish newspaper, Forverts (Forward), reported that the episode had affected the president’s previously-high level of support in the Jewish community: “In open comment it is voiced that Roosevelt has betrayed the Jews.”

THE RESCUE RESOLUTION

Utilizing the drama of the rabbinical march to garner publicity and congressional sympathy for rescue, the Bergsonites persuaded Senator Guy Gillette (D-Iowa) and Representative Will Rogers, Jr. (D-CA) and Joseph Baldwin (R-NY) to introduce a resolution urging the creation of a U.S. rescue agency. The Roosevelt administration opposed the resolution, fearing the rescue campaign would increase pressure to let refugees come to the United States.

When Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long was unable to dissuade members of Congress from introducing the resolution, the administration tried another strategy. Rep. Sol Bloom, chairman of the House International Affairs Committee and a staunch supporter of the administration’s refugee policy, was enlisted to block the resolution by insisting on full hearings. But this effort backfired when Long gave wildly misleading testimony about the number of refugees who had already been admitted. Long’s misrepresentations sparked widespread media coverage and denunciations from Jewish organizations and Members of Congress. The resolution gained additional momentum in December when it was unanimously approved by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Meanwhile, aides to Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. had uncovered a pattern of attempts by the State Department to obstruct rescue opportunities and block the flow of Holocaust information to the United States. Treasury official Josiah E. DuBois, Jr. drafted a report titled Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews. Armed with the DuBois report and with the full senate preparing to vote on the rescue resolution, Morgenthau went to the president in January 1944 to warn him that the refugee issue had become “a boiling pot on [Capitol] Hill” and Congress was likely to pass the resolution unless the White House acted. With election day just ten months away, Roosevelt pre-empted Congress by establishing the new agency that the resolution had sought–the War Refugee Board.

Morgenthau acknowledged that it was the Bergson group’s work that had created that “boiling pot.” At a Treasury Department staff meeting not long after the creation of the War Refugee Board, discussing the factors that made its creation possible, he remarked: “The tide was running with me….The thing that made it possible to get the President really to act on this thing [was] the [rescue] Resolution [which] at least had passed the Senate to form this kind of a War Refugee Committee, hadn’t it? I think that six months before [the rescue resolution] I couldn’t have done it.”

An editorial in the Christian Science Monitor noted that the establishment of the Board “is the outcome of pressure brought to bear by the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe, a group made up of both Jews and non-Jews that has been active in the capital in recent months.” A Washington Post editorial commented that in view of Bergson’s “industrious spadework” on behalf of rescue, the Emergency Committee was “entitled to credit for the President’s forehanded move.”

THE WAR REFUGEE BOARD: A TURNING POINT

The War Refugee Board marked a profound reversal in U.S. policy regarding European Jewry. Its creation was virtually an admission that “rescue through victory” had been a mistake, and that rescue was possible. The Board never lived up to rescue advocates’ expectations, in part because it was given minimal government funding. But with funds contributed primarily by Jewish groups and a staff composed largely of the same Treasury Department officials who helped lobby for the board’s creation, it energetically employed unorthodox means of rescue. It moved Jews out of dangerous zones, pressured the Hungarian authorities to end deportations to Auschwitz, and sheltered Jews in places such as Budapest, where it financed the work of Swedish rescue activist Raoul Wallenberg.

The Bergson Group, meanwhile, sent Eri Jabotinsky to Turkey in the spring of 1944 to work with War Refugee Board emissaries there. Through frenetic lobbying of Turkish government officials, Jabotinsky helped open escape routes for Jews to get out of Greece and Rumania, and built relationships with the array of boat owners and black marketeers, willing to undertake what the author and Bergson Group activist John Gunther called “Jew-running.” By early 1945, however, Jabotinsky was forced to flee Turkey just ahead of a British arrest warrant related to his ties to the Irgun. Historians estimate that altogether, the War Refugee Board’s efforts played a major role in saving about 200,000 Jews and 20,000 non-Jews.

When the Board began pressing President Rooesvelt to establish temporary havens in the United States for refugees, the Bergson Group helped galvanize public opinion in favor of the idea by taking out numerous full-page newspaper ads. In the end, however, FDR agreed to admit one token group of 982 refugees outside the quota system–but no others. The journalist (and Bergson Group supporter) I.F. Stone called Roosevelt’s gesture “a bargain-counter flourish in humanitarianism.”

The Bergson Group also made several proposals to the administration for unorthodox military action to aid Europe’s Jews. In July 1944, it sent a letter to the president, urging bombing raids on the death camps and the railway tracks leading to them. The Bergsonites also proposed that the Allies use poison gas against the Germans, in retaliation for the mass gassing of Jews. Both suggestions were rejected.

THE FIGHT FOR JEWISH STATEHOOD

In early 1944, the Bergson Group launched two new political action committees. The American League for a Free Palestine sought to mobilize American public support for creation of a Jewish state. It utilized familiar Bergson Group tactics, such as full page newspaper advertisements, rallies, lobbying in Washington, and theatrical performances. A play authored by Ben Hecht and produced by the ALFP, “A Flag is Born,” took Broadway by storm in the autumn of 1946. Starring Paul Muni and a young Marlon Brando, “Flag” highlighted the struggle of Holocaust survivors to reach Palestine. It raised funds that the Bergsonites used to purchase a ship to bring 800 European Jewish refugees to Palestine, only to be intercepted by the British.

A Mexican division of the League, headed by Sidney Kluger, raised funds, smuggled weapons to the Irgun Zvai Leumi in Palestine, and published La Respuesta, a Spanish-language edition of the Bergson Group’s newspaper, The Answer. A Canadian branch, led by Samuel and Betty Dubiner, carried on educational activities and recruited several hundred volunteers for a “Maple Leaf Legion,” who reached Palestine on the S.S. Altalena (see below) and joined up with the Irgun.

One of the American League’s most controversial actions was a full-age ad, headlined “Letter to the Terrorists of Palestine,” written in the form of a letter from Hecht to the Irgun Zvai Leumi. Hecht did not agree with the British characterization of the Jewish fighters were terrorists; he used it as a literary device. The ad asserted that American Jews were cheering for the rebels. “Every time you blow up a British arsenal [in Palestine],” Hecht wrote, “or wreck a British jail, or send a British railroad train sky high, or rob a British bank or let go with your guns and bombs at the British betrayers and invaders of your homeland, the Jews of America make a little holiday in their hearts.” In response, British Embassy officials in Washington sought–unsuccessfully–to convince the Truman administration to deport Bergson, revoke the Bergson Group’s tax-exempt status, or at least prohibit government employees from publicly endorsing the group.

Shortly after the ALFP was created, the Bergsonites established the Hebrew Committee of National Liberation, patterned on the various governments-in-exile that had been operating since the German conquest of continental Europe. The HCNL purported to represent the Jewish community of Palestine and European Jewish refugees seeking to reach Palestine. This put the Bergsonites in direct conflict with the Jewish Agency, which claimed to represent Palestine Jewry.

Bergson’s insistence on using the word “Hebrew” instead of “Jew” further complicated matters. A small group of strongly secular Zionists in Mandatory Palestine subscribed to an ideology, often called Canaanism, which regarded the ancient Canaanite nation, rather than Diaspora Jewry, as the true forebears of the Jewish community of Palestine. Some Bergson Group leaders felt an affinity for this perspective, and argued that Palestine Jewry and European Jewish refugees seeking to reach Palestine constituted a new “Hebrew” nation that was distinct from Jews in the Free World. Bergson’s promotion of this philosophy caused confusion among some of his supporters and invited ridicule from his critics.

BERGSON’S OPPONENTS

Long before the establishment of the Hebrew Committee, the Bergson Group faced substantial opposition from mainstream Jewish organizations, the British government, and the Roosevelt administration.

Some Jewish leaders feared the Bergson Group’s growing prominence was usurping their position in the Jewish community and in the eyes of government officials. They also worried that the Bergson group’s public criticism of America’s refugee policy could provoke antisemitism, and that U.S. Jews might be accused of undermining the government during wartime. Several of the major Jewish organizations tried, but for the most part failed, to persuade figures of prominence to cut their ties with the Bergson Group. They also pressed some publications to refuse Bergson’s advertisements. Congressman Bloom and several Jewish leaders privately urged the State Department to have Bergson deported or drafted, and to have the FBI and IRS investigate the group. Nahum Goldman, co-chair of the World Jewish Congress, told State Department officials in 1944 that Rabbi Stephen Wise regarded Bergson as “equally as great an enemy of the Jews as Hitler” because he believed Bergson’s activities would increase antisemitism in the United States.

The British, who dubbed Bergson “a Semitic Himmler,” likewise urged U.S. officials to draft or deport Bergson. Deporting Bergson to Palestine would make it possible for the British to arrest him for belonging to the Irgun, an illegal organization. But London thought the chances of that happening were unlikely “in view of the influential friends who seem to be able to protect him.” Counter-pressure from Bergson’s allies in Congress, combined with the State Department’s fear that such action would “make a martyr out of Bergson,” stymied consideration of taking serious steps against him.

The Roosevelt administration sent the FBI and the Internal Revenue Service after Bergson. “This man has been in the hair of Cordell Hull,” an internal FBI memo noted in 1944, explaining the reason for U.S. government action against Bergson. The FBI eavesdropped on the telephone conversations of Bergson activists, opened their mail, sifted through their trash, and used informants to gather information and take documents from Bergson’s office, searching for evidence that the activists were either Communists or connected to terrorism in Palestine. They found neither. The IRS searched for financial irregularities that would enable the administration to revoke Bergson’s tax-exempt status. IRS agents repeatedly visited the Bergson group’s office, but ultimately uncovered nothing untoward.

After the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the Bergson committees voluntarily dissolved. Merlin and Kook had been involved in organizing the Irgun weapons ship Altalena, and Merlin was aboard the ship when it approach the Tel Aviv shore and was attacked by Haganah gunners. Merlin was wounded in the leg and limped for the rest of his life. Kook, who arrived in the country by plane at about the same time, was arrested by the Haganah and imprisoned for three months. Merlin, Kook, and Jabotinsky subsequently served in Israel’s parliament as representatives of Menachem Begin’s Herut Party from 1949 to 1952. Afterwards they returned to private life, Jabotinsky as a mathematics instructor, Kook as an investment specialist, and Merlin as head of the Institute for Mediterranean Affairs, a small think tank in New York City.

Sources: Wyman and Medoff, A Race Against Death, pp.13-55;

Baumel, The ‘Bergson Boys,’ pp.197-248;

Penkower, The Holocaust and Israel Reborn, pp.61-90.

Video Interview (Spielberg Film Archive)