A rising tide of calls in the British parliament, media, and churches for Allied assistance to Jewish refugees in early 1943 prodded the British Foreign Office and the State Department to plan an Anglo-American conference on the refugee problem. They initially chose Ottawa as the site for the event, but did so without consulting the Canadian government, and were forced to look elsewhere when the Canadians objected. London and Washington were ruled out as being too accessible to protesters.

Eventually, the island of Bermuda, far from the prying eyes of demonstrators and the news media, was chosen. Zionist leader Nahum Goldmann surmised that the remote setting was selected so that “it will take place practically in secret, without pressure of public opinion.”

Like the Evian conference five years earlier, Bermuda was born of the Allies’ desire to appear to be concerned about the refugees without actually taking meaningful steps to alleviate the Jews’ plight. Commenting on the Bermuda organizers’ strategy, Jewish Agency official Arthur Lourie noted that “the whole procedure adopted by the British and American Governments with regard to the refugee question is directed towards quieting public opinion without undertaking anything effective.”

The Joint Emergency Committee of European Jewish Affairs, a recently-established umbrella for the major U.S. Jewish organizations, requested permission to send a delegation to the conference. The request was rejected. The JEC then presented Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles with a list of proposals for rescue action. The proposals were ignored. A group of seven Jewish congressmen likewise sought to press the administration on rescue issues in advance of the Bermuda gathering.

President Roosevelt initially declined to see them, relenting only after strong pressure by Rep. Emanuel Celler. They met with the president at the White House on April 1. “It was a very unsatisfactory interview,” Congressman Daniel Ellison (R-Maryland) reported. “[We] asked the President about refugees, the White Paper, etc. What he proposed to do about these things. [We] made a number of suggestions to him as to what [we] thought he ought to do and the answer to all of these suggestions was ‘No’.” Roosevelt hinted that “perhaps visitor’s visas would again be issued” for refugees as he had done after the 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom; in fact, however, FDR never repeated that action.

State Department officials briefed President Roosevelt once during the preparations for the conference. After that, FDR showed almost no interest in the subject, except to unsuccessfully urge Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts to chair the U.S. delegation. Roosevelt told Roberts he regretted the justice “cannot go to Bermuda—especially at the time of the Easter lillies!” Princeton University president Harold W. Dodds ultimately agreed to take the post. He was joined on the delegation by Senator Scott Lucas (D-Illinois) and Congressman Bloom. R. Borden Reams, one of the State Department’s fiercest opponents of rescue, was named secretary of the delegation.

The selection of Bloom was regarded by Jewish organizations as a bad omen. Nahum Goldmann warned his colleagues that Bloom had been chosen to serve as “an alibi” for the likely refusal of the conferees to take real action. Indeed, Breckinridge Long privately regarded Bloom as “easy to handle” and “terribly ambitious for publicity,” two qualities that would ensure he would do as the State Department asked. American Jewish Congress leader Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, who had derided Bloom as “the State Department’s Jew” prior to his participation in the U.S. delegation to the 1938 Evian conference, expected a repeat performance from the congressman.

The Bermuda conference opened on April 19, 1943. The American delegates’ terms of reference guaranteed that no significant action would emerge from Bermuda. There was to be no special emphasis on the plight of the Jews, nor any policies adopted that would benefit Jews in particular.

The U.S. would not agree to the use of any trans-Atlantic ships to transport refugees, not even troop supply ships that were returning from Europe empty. There would be no increase in the number of refugees admitted to the United States.

The British delegates, for their part, refused to discuss Palestine as a possible refuge, because of what Nahum Goldmann called “[their] policy, both foolish and immoral, of appeasing Arab Nazis.” The British also shut down the idea of negotiating with the Nazis for the release of Jews, on the grounds that “many of the potential refugees are empty mouths for which Hitler has no use.” (“ ‘Potential corpses’ would be a more appropriate term” than “potential refugees,” one Jewish activist commented.) Their release “would be relieving Hitler of an obligation to take care of these useless people.” The delegates also rejected the idea of food shipments to starving Jews as a violation of the Allied blockade of Axis Europe, even though they had previously made an exception for German-occupied Greece. All of these limitations left the delegates at Bermuda spending a large amount of time on very small-scale steps, principally the evacuation of 5,000 Jewish refugees from Spain to the Libyan region of Cyrenaica.

Having achieved next to nothing, the two governments kept the proceedings of the conference secret, which only generated further suspicion. A message sent by Assistant Secretary of State Adolph Berle to a Jewish rally in Boston two days after Bermuda’s conclusion reiterated the main underlying theme of the conference: “Nothing can be done to save these helpless unfortunates” except to win the war he asserted.

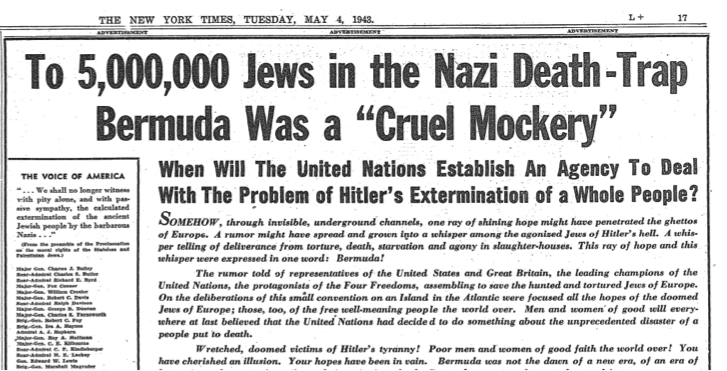

The failure of the Bermuda conference provoked the first serious public criticism of the administration’s refugee policy. The response that generated perhaps the most attention was a large advertisement sponsored by the Bergson Group in the New York Times on May 4, headlined “To 5,000,000 Jews in the Nazi Death-Trap, Bermuda was a Cruel Mockery.” Coming just three days after the conference ended, the ad helped set the tone for other responses.

Congressman Samuel Dickstein (D-NY), chairman of the House Immigration Committee, declared: “Not even the pessimists among us expected such sterility.” Congressman Celler accused the delegates in Bermuda of engaging in “more diplomatic tight-rope walking,” at a time when “thousands of Jews are being killed daily.” Celler pointedly characterized Bermuda as “a bloomin’ fiasco,” a thinly-disguised slap at Sol Bloom, who had remarked, “As a Jew, I am perfectly satisfied with the results of Bermuda.”

One American Zionist publication charged that Bloom was “used as a stooge to impede Jewish protests against the nothing-doers of the Bermuda Conference.” Jewish activist Peter Bergson later recalled that when he met with Bloom shortly after the conference, the congressman “told me that he took along matzohs when he left for Bermuda—it was the Passover season—because he was such a good Jew. So I told him that I thought it would have been more important for him to eat bread there and save some Jews rather than to eat matzohs. He was very angry and told me was through talking to me.”

Some mainstream Jewish leaders were equally outspoken. Dr. Israel Goldstein, president of the Synagogue Council of America (the umbrella for the major Jewish religious denominations) blasted the conference as “not only a failure, but a mockery,” and bluntly added that “the victims are not being rescued because the democracies do not want them, and the job of the Bermuda conference apparently was not to rescue victims of Nazi terror but to rescue our State Department and the British Foreign Office from possible embarrassment.” The Joint Emergency Committee was slow to respond; it took more than a month to compose its official statement. But when it did, it went further than any of its member-organizations had previously gone in challenging U.S. policy. Directly challenging the administration’s “rescue through victory” philosophy, the JEC stated: “To relegate the rescue of the Jews of Europe, the only people marked for total extermination, to the day of victory is…virtually to doom them to the fate which Hitler has marked out for them.” Rabbi Wise characterized the Bermuda parley as “a woeful failure,” although he was careful to avoid blaming President Roosevelt.

Sources: Wyman, The Abandonment of the Jews, pp.104-123;

Penkower, The Jews Were Expendable, pp.98-123;

Feingold, The Politics of Rescue, pp.167-207.