Media magnate William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951) strongly supported the campaign for U.S. action to rescue Jews from the Holocaust.

In his early years, Hearst occasionally uttered the kind of antisemitic remarks typical of the late 19th century upper-crust Protestant society.

By the 1890s, however, Hearst’s New York Journal was strongly supporting the Jewish immigrant community and forcefully criticized antisemitism. After the 1903 Kishinev pogrom in Czarist Russia, the Hearst newspaper chain collected nearly $50,000 –a substantial sum for that time– for the Kishinev Relief Committee. The Hearst papers also commissioned the most comprehensive on-site investigation of the massacre, and even hinted that the United States should consider declaring war on Russia.

Hearst’s sensationalist style of journalism, strong attacks on President Roosevelt and the New Deal, and pre-World War II isolationism made him anathema to much of the American Jewish community. Hearst’s publication of articles by both Hitler and Mussolini reinforced his image among American Jews as an unpalatable reactionary.

Hearst visited Nazi Germany in 1934 and met with Hitler. Although he divulged few details of the meeting at the time, some of Hearst’s subsequent public remarks about the situation in Germany exhibited a naive acceptance of Hitler’s claim that there was no anti-Jewish discrimination there. In Hearst’s account of the meeting, first published after his death, he claimed his friend Louis B. Mayer, the Jewish Hollywood producer, had urged him to meet Hitler in order to press him to curb his anti-Jewish policies. According to Hearst, he did indeed challenge Hitler on his treatment of the Jews.

Kristallnacht appears to have been a turning point for Hearst. The pogrom convinced Hearst that Hitler was “making the flag of National Socialism a symbol of national savagery.” After Kristallnacht, Hearst began advocating creation of “a homeland for dispossessed or persecuted Jews.” When news of the mass murder of Europe’s Jews began reaching the United States in 1941-1942, the Hearst newspaper chain gave it prominent coverage, by contrast with newspapers such as the New York Times, which routinely confined it to the back pages.

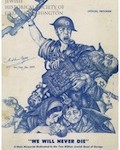

In 1943, Hearst served as an honorary chairman of the Bergson Group’s Emergency Conference to Save the Jewish People of Europe. When the Bergsonites in late 1943 initiated a congressional resolution urging FDR to create a government agency to rescue Jewish refugees, Hearst directed his newspaper chain to promote the resolution and he personally authored signed editorials endorsing it. One declared: “Remember, Americans, this is not a Jewish problem. It is a human problem.”

“Hearst was the only newspaper owner who supported us without any qualifications or reservations,” Samuel Merlin, a leader of the Bergson Group, said in a postwar interview. “All his papers. He gave us pages after pages free. He gave us the whole editorial page–Hearst himself. He gave orders to print our material.” The group’s leader, Peter Bergson (Hillel Kook), noted that he and his colleagues endured some criticism because of their relationship with Hearst: “We were even attacked as ‘fascists’ because we approached William Randolph Hearst several times,” he recalled. “What right did we have to decide who should save the Jews? For God’s sake, we would go to anybody. I mean, would we need a rabbi to say ‘Save the Jews’? We were delighted that we got Hearst to say ‘Save the Jews’.” The support of Hearst’s thirty-four newspapers gave the congressional resolution an important boost, helped keep the refugee issue in the public eye, and focused negative attention on the Roosevelt administration’s opposition to rescue action.

Sources: Nasaw, The Chief, pp.70-71, 488-489;

Wyman and Medoff, A Race Against Death, pp.76-77.