Soon after the United States entered World War II, the Roosevelt administration began planning for the arrest and postwar prosecution of Nazi war criminals. Even at that early stage, the Allies knew enough about Nazi atrocities against Jews and others to know that if and when they won the war, they would have many war criminals on their hands. Yet U.S. policy on what to do with those war criminals was ambivalent.

In 1942, President Roosevelt publicly pledged that Nazi war criminals would be punished. The following year, the Allies established a United Nations War Crimes Commission and FDR appointed his old friend Herbert C. Pell (1884-1961), a former congressman and former U.S. minister to Portugal, as the U.S. representative to the commission.

The State Department wanted to limit postwar trials to only the most prominent and notorious war criminals, for fear that prosecuting large numbers of Germans could harm America’s relations with Germany after the war. Pell, however, favored prosecuting all Nazi war criminals, a stance that brought him into repeated conflicts with State Department officials. The State Department sent one of its staff members to meetings in London of the commission in order to shadow Pell and secretly report back to Washington on positions Pell was taking.

During a visit to Washington in late 1944 to attend his son’s wedding, Pell met with President Roosevelt, who voiced support for Pell’s efforts on the commission. FDR did not mention what he already knew, and what Pell was informed by the State Department later that day–that his service had been terminated because it could no longer find $30,000 in its budget to fund his position. Pell promptly offered to work for free; State replied that it would be illegal for him to work without being paid.

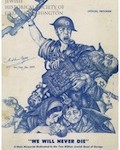

Pell turned to the Bergson Group to help him publicize the scandal. At a press conference in New York City organized by Bergson’s Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe in January 1945, Pell blew the story wide open. He urged punishment of “every Gestapo member who has caused suffering,” denounced the State Department for leaving his proposals “to gather dust in the files of its legal adviser,” and labeled as “nonsense” the State Department’s explanations for his termination. “If we are not tough and hard toward the war criminals,” he explained, “it will encourage other tyrants to try the same thing–to murder, persecute and loot from minorities. Conviction and punishment of Axis war criminals is not a matter of revenge. It is justice.”

The Pell scandal appeared on the front page of the New York Times and throughout the American press. Embarrassed by the avalanche of negative publicity, the State Department was forced to reconsider its position. Within days, Acting Secretary of State Joseph Grew announced a complete reversal of its previous position–the State Department now agreed that Nazi murderers of European Jews should be prosecuted.

Twenty-four of the most prominent war criminals were put on trial by the Allies in a series of military tribunals in the German city of Nuremberg in 1945-1946. Nineteen were convicted, of whom twelve were sentenced to death.

Twelve additional trials, of lesser-known war criminals, were held between 1946 and 1949. Of those 185 defendants, 142 were convicted. But as time went on, the United States showed less and less interest in bringing war criminals to trial. And many of those who had been convicted and jailed were soon set free, thanks to John J. McCloy, who became U.S. High Commissioner for Germany in 1949.

One hundred and four German industrialists were convicted of war crimes, and 84 were still in jail when McCloy arrived in Germany. Of those 84, McCloy reduced the sentences of 74 to time already served, thus setting them free immediately.

Sources: Wyman, The Abandonment of the Jews, pp.257-260;

Medoff, Blowing the Whistle on Genocide, pp.105-112.