Beginning in the late spring of 1944, representatives of Jewish organizations in the United States, Europe, and British Mandatory Palestine began urging Allied officials to take military action to interrupt the mass murder of Jews in Auschwitz. About thirty different Jewish officials were involved, at one time or another, in advocating such Allied intervention. Generally, these requests were made in private meetings with Allied officials; only on a few occasions were they articulated in public.

Jewish requests for Allied military action included three possible avenues: bombing the railway tracks and bridges over which hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were then being deported to Auschwitz; bombing the gas chambers and crematoria within Auschwitz; and sending Allied ground troops or Polish underground forces to directly attack the camp.

The Jewish leaders addressed their appeals to American, British, and Soviet diplomats, as well as to the Polish and Czech governments in exile.

Only one official of one organization specifically opposed any of these methods. A. Leon Kubowitzki of the World Jewish Congress favored bombing the railways and bridges, but recommended using ground troops rather than air strikes, to destroy the gas chambers, because of the possibility of civilian casualties in the camp. After the war, Kubowitzki seemed to regret having opposed bombing, confiding to a colleague: “With regard to the bombing of the death camps and many other questions, there is no doubt that I did not have as much information as I needed.” Other Jewish officials weighed the risk of casualties and concluded that bombing was nevertheless justified, because the camp inmates were doomed to be murdered imminently.

Bombing the railway tracks and bridges had the advantage of involving relatively little risk to Allied servicemen, and the U.S. was already bombing railways and bridges throughout Europe as part of the war effort. Although the Germans were sometimes able to repair damaged track lines within hours, repairing bridges took much longer. With regard to a possible bombing of the gas chambers and crematoria, it was impossible to predict how successful Allied bombers would be in carrying out precision attacks on those targets. However, in a somewhat similar raid on an arms factors in the Buchenwald concentration camp in August 1944, the American bombers succeeded in avoided adjacent prisoners’ barracks.

The proposal to send ground troops was the most ambitious. Almost certainly it would have involved casualties to the attacking forces, and for that reason it was the proposal least likely to be accepted by Allied military commanders and political leaders. Moreover, requesting an attack by ground troops played to one of American Jewish leaders’ worst fears: the accusation that Jews were willing to risk the lives of Allied soldiers for their own narrow interests.

THE ROOSEVELT ADMINISTRATION’S POSITION

As a matter of principle, the Roosevelt administration strongly opposed taking any special action to aid Jewish refugees. The administration’s declared policy, until early 1944, was “rescue through victory,” that is, rescue of Jews could be accomplished only through victory over the Germans on the battlefield.

In early 1944, in response to strong pressure from Congress, Jewish groups, and the Treasury Department, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established a new government agency, the War Refugee Board, which in theory represented a new U.S. policy of aiding refugees even before the end of the war. But in reality, the Board was established against the administration’s wishes. FDR created the WRB in response to intense pressure from members of Congress, Jewish activists, and his own Treasury Department. The administration gave the Board only minimal funding (90% of its budget was provided by private Jewish orrganizations), and the State Department and War Department, which officially were required to cooperate with the Board, did so only infrequently at best.

Long before the first Jewish request for military intervention was made, senior officials of the War Department had decided that they would have nothing to do with aiding refugees. In response to the creation of the War Refugee Board, the War Department assured the British government (which was opposed to Allied intervention on behalf of the Jews): “It is not contemplated that units of the armed forces will be employed for the purpose of rescuing victims of enemy oppression unless such rescues are the direct result of military operations conducted with the objective of defeating the armed forces of the enemy.”

Internal War Department memoranda the following month stated unequivocally that “the most effective relief which can be given victims of enemy persecution is to insure the speedy defeat of the Axis.” This attitude would govern the War Department’s response to Jewish requests in the months to follow.

On June 18, 1944, Rabbi Yaakov Rosenheim, president of a New York-based Orthodox Jewish organization, Agudath Israel, wrote to the War Refugee Board, urging bombing of the railways to Auschwitz. The request was based on a bombing appeal that had reached him from Slovakian rescue activist Rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandl. WRB director John Pehle relayed Rosenheim’s request to Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy.

Two days later, before Rosenheim heard back from McCloy, he sent Agudath Israel representative Meir Schenkelowski to Washington to promote the proposal in person. Schenkelowski met with Secretary of State Cordell Hull, who declined to consider the proposal, suggesting that Schenkelowski speak with Secretary of War Henry Stimson instead. He met Stimson shortly afterwards. The war secretary responded that the area was a zone of Soviet responsibility and therefore a bombing decision was up to Moscow.

In fact, the U.S. was already bombing German oil factories in the industrial section of Auschwitz. Hull and Stimson were the highest ranking U.S. officials known to have considered the bombing proposal. No documents have been found to indicate that the bombing requests reached President Roosevelt himself.

On June 24, the U.S. Minister to Switzerland, Leland Harrison, sent a telegram to Secretary Hull, recommending the bombing of railways leading to Auschwitz and giving precise locations of desired bombing targets. On June 29, John Pehle relayed Harrison’s request to Assistant Secretary McCloy.

On July 4, McCloy responded to the Rosenheim and Harrison requests. In a note to Pehle, he claimed that the War Department had carried out a “study” of the feasibility of such bombing raids. However, historians have never been able to locate a copy of any such study in the relevant archives.

McCloy further wrote that bombing the railways was “impracticable” because it would require “the diversion of considerable air support essential to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations…”

In fact, the Allies were already operating in the skies above Auschwitz and did not have to be “diverted” from elsewhere in order to reach the death camp. Since April 4, Allied planes had been carrying out photo reconnaissance missions in the area around Auschwitz, in preparation for attacking German oil factories and other industrial sites in the region, some of which were situated just a few miles from the gas chambers and crematoria.

THE JEWISH AGENCY’S POSITION

Meanwhile, some Jewish leaders in British Mandatory Palestine were discussing the bombing idea as well. On June 2, 1944 Yitzhak Gruenbaum, chairman of the Rescue Committee of the Jewish Agency–the governing authority for the Jewish community in Palestine–met with the U.S. consul-general in Jerusalem, Lowell C. Pinkerton. Gruenbaum explained the rationale for bombing Auschwitz and the railways leading to it, and asked to send a telegram to that effect to the War Refugee Board.

On June 11, Gruenbaum described his conversation with Pinkerton to a meeting of the Jewish Agency Executive (JAE), in Jerusalem. The meeting was chaired by David Ben-Gurion, chairman of the JAE and future prime minister of Israel. Although some internal Jewish Agency documents prior to June 1944 had mentioned mass murder in Auschwitz, the information was not fully understood or absorbed by all the members of the executive.

Ben-Gurion said in the June 11 meeting that he opposed asking the Allies to bomb it because “we do not know what the actual situation is in Poland.” Another JAE member, Emil Schmorak, opposed requesting bombing because “It is said that in Oswiecim [the Polish name for Auschwitz] there is a large labor camp. We cannot take on the responsibility for a bombing that could cause the death of even one Jew.” Instead of a vote, Ben-Gurion concluded the discussion by stating that the consensus of the participants was that “it is the position of the Executive not to propose to the Allies the bombing of places where Jews are located.”

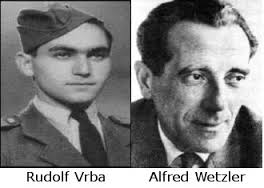

The Jewish Agency’s position soon changed. On June 19, 1944 the head of the Agency’s office in Geneva, Richard Lichtheim, wrote a five-page letter to Gruenbaum summarizing detailed information about Auschwitz that had been provided by two recent escapees from the camp, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler. Lichtheim explained to his Jerusalem colleagues that the information showed the Agency’s previous information about Auschwitz being a labor camp was erroneous.

“We now know exactly what has happened and where it has happened,” Lichtheim wrote. “There IS a labour camp in [the] Birkenau [section of Auschwitz] just as in many other places of Upper Silesia, and there ARE still many thousands of Jews working there and in the neighbouring places (Jawischowitz etc). But apart from the labour-camps proper [there are] specially constructed buildings with gas-chambers and crematoriums….The total number of Jews killed in or near Birkenau is estimated at over one and a half million….12,000 Jews are now deported from Hungary every day. They are also sent to Birkenau. It is estimated that of a total of one million 800,000 Jews or more so far sent to Upper- Silesia 90% of the men and 95% of the women have been killed immediately…”

Lichtheim’s letter, together with the Vrba-Wetzler report, reached Gruenbaum in Jerusalem during the last week of June, and reached Jewish leaders in New York City shortly afterwards. A. Leon Kubowitzki, head of the Rescue Department of the World Jewish Congress, had, like his colleagues in Palestine, apparently not fully understood the nature of Auschwitz-Birkenau. “Shocked by Birkenau extermination,” Kubowitzki cabled a colleague in London on July 5. “Were convinced Birkenau only labor camp.”

During the weeks following receipt of the report, Jewish Agency officials in Europe, the Middle East, and the United States began promoting the bombing proposal.

The president of the Jewish Agency and World Zionist Organization, Chaim Weizmann, together with Moshe Shertok, the head of the Agency’s Political Department (and also a future Israeli prime minster), met on June 30, 1944 with British Undersecretary of State for Foreign Affairs George Hall and urged that “death camps should be bombed.” On July 6, Weizmann and Shertok met with British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, and urged the bombing of both the railways and “the death-camps at Birkenau and other places.” Afterwards, Shertok sent Ben-Gurion a telegram reporting that Eden was “very sympathetic” to idea of bombing “death camps and railway lines leading to Birkenau.”

At the same time, Jewish Agency representatives in Washington (Nahum Goldmann), London (Joseph Linton and Berl Locker), Geneva (Richard Lichtheim and Chaim Pozner), Cairo (Eliahu Epstein), Budapest (Moshe Krausz) and Istanbul (Chaim Barlas) met with Allied diplomats and others to make the case for Allied air strikes on Auschwitz or the rail lines leading to the camp.

A number of officials of local Jewish organizations in London (such as Anselm Reiss of the World Jewish Congress, and A.G.Brotman of the Board of Deputies of British Jews) and Geneva (such as Gehart Riegner of the World Jewish Congress) worked closely with Jewish Agency representatives in promoting the bombing idea.

Several Agency representatives reported directly to Ben-Gurion on the matter. For example, in a letter to Ben-Gurion in July, Lichtheim described the latest deportations to Auschwitz and urged “bombing of railways in line leading from Hungary to Birkenau” and “precision bombing of death camp installations.” Likewise Epstein reported to Ben-Gurion about his meeting in Cairo, in July 1944, with a Soviet diplomat to whom he advocated a Soviet bombing of the death camps. The diplomat rejected the request on the grounds that showing favoritism to the Jews would conflict with the Soviet ideology of not distinguishing between ethnic groups.

The issue was discussed at two Zionist leadership meetings in Jerusalem in the early autumn. At a September 5 session of the World Zionist Organization’s Smaller Zionist Actions Committee, Yitzhak Gruenbaum, a member of the committee, remarked that “bombing Oswiecim, destroying Oswiecim, bombing transportation lines” was the only way to save the Jews, “but it is impossible to say such things explicitly and openly in a resolution passed by the Actions Committee.”

On October 3, 1944 at a meeting of the Jewish Agency’s Rescue Committee, Gruenbaum reported in detail on the Agency’s various lobbying efforts for bombing during the preceding months. He said the Agency had, since June, “sent emergency telegrams to all the countries,” urging “first of all, that they bomb Oswiecim, that they should destroy the death camps.” He said that when this demand was first made, “the reply [of Allied officials] was completely negative. They asked if it was acceptable to us that when they bombed the death camps, Jews would be killed. Suddenly these people are worried about the Jews, that they would kill them in the bombings. At the time [the Allies] bombed Budapest, they were not worried about that.” Gruenbaum also noted–evidently alluding to the aforementioned June 11 meeting of the JAE–that “Even among us there were people who thought this was impossible, who had similar reservations.” Gruenbaum’s frank and detailed description, in October, of the months-long lobbying effort was not disputed by any of the attendees, which indicates that the committee members had previously assented, perhaps verbally, to the lobbying activity.

THE POSITION OF THE WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS

Dr. Nahum Goldmann, who served as both the Jewish Agency’s Washington, D.C. representative and co-chairman of the World Jewish Congress, repeatedly contacted U.S., British, Soviet, and other diplomats to, as he put it, “look for a way to destroy these camps by bombing or any other means.” He also wrote to Czech foreign minister in exile Jan Masaryk, asking him to urge Czech president in exile Eduard Benes to “discuss this idea with the Russians.” Goldmann’s deputy, Maurice Perlzweig, also contacted War Refugee Board officials to promote the bombing idea.

One of Goldmann’s other subordinates, the aforementioned A. Leon Kubowitzki, disagreed. Kubowitzki, who served as chairman of the Rescue Department of the World Jewish Congress, wrote John Pehle of the War Refugee Board on July 1 to urge an attack on Auschwitz by Soviet paratroopers and Polish underground forces rather than aerial bombardments, for fear that bombing might harm the inmates. He reiterated this position in an August 2 letter to Ernest Frischer of the Czech Government in Exile, in London. At the same time, however, Kubowtzki also forwarded to McCloy appeals from officials of the Czech and Polish governments in exile, urging the bombing of Auschwitz.

A number of other individual Jewish organizations or officials also contacted Allied representatives to promote bombing. For example, on July 24, 1944 the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe (the Bergson Group) wrote to President Roosevelt, urging bombing of the railways “and the extermination camps themselves.” Roosevelt did not respond. The Group’s representative in Geneva, Reuben Hecht, also spoke with Allied officials to press the bombing idea.

Labor Zionists also took an interest in the issue. Golda Meir, then known as Goldie Myerson, received a number of reports from Europe about the killings, in her capacity as a senior official of the Histadrut, the powerful Jewish labor federation in Palestine. In July 1944, she forwarded one such report to the Histadrut’s U.S. representative, Israel Mereminski, together with an appeal to ask U.S. officials to undertake “the bombing of Oswienzim [sic] and railway transporting Jews” to the death camp. Meir’s appeal was cosigned by another Histadrut official, Heschel Frumkin. Mereminski replied that he contacted the War Refugee Board, which in turn submitted “to competent authorities” the Meir-Frumkin request for “destruction gas chambers, crematories, and so forth.”

Shortly afterwards, the August 1944 issue of Jewish Frontier, a U.S. Labor Zionist journal with which Mereminski was closely associated, published an unsigned editorial calling for “Allied bombings of the death camps and the roads leading to them…” The Jewish Frontier editorial was the first instance in which a U.S. Jewish organization went public with its demand for the bombing of the death camps. The Meir-Mereminski contacts may have prompted the editorial.

On July 31, the American Jewish Conference, a coalition of major Jewish organizations, held a rally at Madison Square Garden to appeal for Allied intervention on behalf of Hungarian Jewry. The organizers adopted an eight-point plan for rescue, which had been formulated primarily by officials of the World Jewish Congress. Point number eight read: “All measures should be taken by the military authorities, with the help of the underground forces, to destroy the implements, facilities, and places where the Nazis have carried out their mass executions.”

The WJCongress announced on August 14 that it had sent a similar, 11-point rescue plan to its London office to present to Allied officials at an upcoming session of the Intergovernmental Committee for Refugees. Point #11 stated: “That immediate measures be adopted to destroy the murder installations and facilities of the extermination camps.”

BOMBING OF THE AREA AROUND AUSCWHITZ

Despite the War Department’s claim that reaching Auschwitz would require diverting planes from elsewhere in Europe, U.S. bombers repeatedly attacked German oil factories near the death camp throughout the summer.

On July 7, 1944 American bombers began attacks on the Blechhammer oil factories, forty-seven miles from Auschwitz. Nine more such raids took place between July and November.

On August 7, U.S. bombers attacked the Trzebinia oil refineries, just thirteen miles from Auschwitz.

Between August 7 and August 29, there were additional U.S. bombing raids on oil refineries within forty-five miles of Auschwitz.

On August 20, a squadron of 127 U.S. bombers, accompanied by 100 Mustangs piloted by the all-African American unit known as the Tuskegee Airmen, struck oil factories less than five miles from the gas chambers.

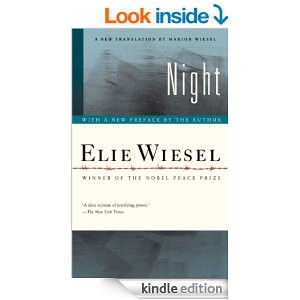

Auschwitz prisoner Elie Wiesel, age 16, witnessed the attack and later wrote about it in his best-selling memoir, Night.

Other Allied planes overflew Auschwitz that summer, but for a different reason. On August 8, Britain’s Royal Air Force began air-dropping supplies to the Polish Home Army rebels in Warsaw. The flight route between the Allied air base in Italy and Warsaw took the planes within a few miles of Auschwitz. They flew that route twenty-two times during the two weeks to follow.

In September, President Roosevelt ordered U.S. planes to take part in the Warsaw airlift mission. The last and largest air- drop took place on September 18, when a fleet of 107 U.S. bombers dropped more than 1,200 containers of weapons and supplies into Warsaw. Less than 300 of the containers reached the Polish fighters; the Germans intercepted the rest.

Yet on August 14, 1944 in response to the continued bombing requests, Assistant Secretary McCloy wrote to A. Leon Kubowitzki that “after a study,” the War Department found bombing the camp or railways “could be executed only by the diversion of considerable air support necessary to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations elsewhere.” McCloy also asserted that such bombing “might provoke even more vindictive action by the Germans.” Kubowitzki replied, to no avail, that “it is difficult to imagine any vindictive action by the Germans which could still deteriorate the present desperate plight of the Jewish population in occupied Europe.” He also scaled down the request for ground forces, suggesting that the paratroopers “should be members of the Allied forces who would volunteer for this task” rather than be required to participate; McCloy replied that Kubowitzki should contact Allied military commanders in Europe.

As for the claim that the War Department carried out a “study” of the feasibility of bombing, repeated attempts by researchers have never turned up any evidence that it was ever undertaken.

THE WAR REFUGEE BOARD’S POSITION

When War Refugee Board director John Pehle forwarded the very first request for bombing the railways to the War Department, in June, he emphasized to Assistant Secretary McCloy that he was not endorsing the request, but merely asking the War Department to “explore” it. Pehle had “several doubts” about whether the proposal was feasible and whether it was “appropriate to use military planes and personnel for this purpose.” He likewise forwarded subsequent bombing requests to the War Department without specifically endorsing them.

Pehle was especially unenthusiastic about Kubowitzki’s proposal for an attack by ground troops, and in fact refused to forward such requests to the War Department. He felt it was “not proper” to ask the War Department even to consider “a measure which involved the sacrifice of American troops.”

One Board staff member who strongly favored bombing both the railways and the camps was Benjamin Akzin, formerly a senior Revisionist Zionist activist. In a June 29 inter-office memo, Akzin acknowledged that the bombings would cause casualties among the inmates, “but such Jews are doomed to death anyhow.”

Despite his initial misgivings, Pehle met in mid-July with Undersecretary of State Edward Stettinius to discuss the possibility of a presidential endorsement of military intervention. After the meeting, the WRB staff drafted a proposed memo from Secretary of State Hull to President Roosevelt, asking him to order military commanders to give “serious consideration” to “some sort of military operations” to stop the mass murder. The memo was evidently blocked in the State Department, although it is not clear by whom.

In August 1944, however, Pehle remarked at a meeting of American Jewish leaders on August 16 that “Jewish organizations” themselves had objected to the idea of bombing the death camps because of civilian casualties. Since there is no record of any such objections made to Pehle except by Kubowitzki, it seems likely that either Pehle was conflating Kubowitzki’s multiple letters, or the stenographer recording the meeting erred. Pehle also poured cold water on Kubowitzki’s idea for the Polish underground to stage an attack, saying he “doubt[ed] that the Poles could muster the strength for such engagements.”

Later, Pehle forcefully advocated bombing. In early November 1944, he belatedly received the full text of the Vrba-Wetzler report. Deeply troubled by the details of the mass murder process, he sent the report to McCloy with an appeal of his own for U.S. military intervention. “Until now, despite pressure from many sources, I have been hesitant to urge the destruction of these camps by direct, military action,” he wrote. “But I am convinced that the point has now been reached where such action is justifiable…” He specifically recommended bombing the camp from the air, and as evidence that some inmates might escape, he cited an article about an Allied air raid to free French prisoners, which Kubowitzki had sent him.

THE FINAL APPEALS FOR BOMBING

The autumn of 1944 saw no let-up in the Jewish leadership’s interest in Allied military intervention against Auschwitz. They may have been encouraged by a September 15 letter from Ernest Frischer of the Czech government in exile that “fuel factories” in the vicinity of Auschwitz had been “repeatedly bombed” recently. In a U.S. bombing raid just two days earlier, stray bombs accidentally hit an SS barracks, killing fifteen Germans, and a slave labor workshop, killing forty prisoners, and damaging a railroad track leading to the camp.

In late September 1944, Kubowitzki sent letters to McCloy and Czech minister Jan Masaryk, again asking for “operational and underground forces” to attack “Oswiecim, Buchenwalde, and Birkenau concentration camps.” Kubowitzki made the same request in a meeting with a Soviet diplomat in Washington on September 28, adding a proposal that the Soviets bomb a number of “railroad hubs” in Hungary in order to “paralyze the deportation movements by railroad.” Nahum Goldmann also tried once more. In October, he met with General John Dill of the Allied High Command to urge bombing of the camps. Dill replied that the Allies “had to save bombs for military targets.”

Unaware that the mass murder at Auschwitz had ceased by early November, Jewish leaders continued pressing the bombing idea. On January 18, 1945, Yitzhak Gruenbaum sent a telegram to Soviet leader Josef Stalin, urging the Soviets to bomb Auschwitz. On January 25, Jewish Agency official Berl Locker, in London, informed Gruenbaum that he had given a local Soviet diplomat a copy of Gruenbaum’s appeal to Stalin. The Soviets did not respond.

In the meantime, the Allies, including the Soviets, were still bombing the Auschwitz region. On December 18 and 26, there were additional U.S. bombing raids on oil refineries in the area. On December 23, the Soviets bombed the Auschwitz area; thirty percent of the SS barracks at Birkenau were destroyed, and the railway link between Auschwitz and Birkenau was severed. On January 16, 1945, the Soviets bombed oil refineries next to Auschwitz. On January 19, there were additional U.S. and Soviet bombing raids on oil refineries in the area. The next day, an Allied bombing raid on the Blechhammer oil refinery, forty-seven miles from the Auschwitz gas chambers, enabled forty two slave laborers to escape. One week later, Soviet troops liberated the camp.

HISTORIOGRAPHY

The subject of the Allies’ refusal to attack the death camps surfaced only sporadically in the first decades after the Holocaust. Memoirs by survivors, such as Olga Lengyel (Five Chimneys, 1947), Charlie Coward (The Password is Courage, 1954), Primo Levi (If This is a Man, 1959), and the then little-known Elie Wiesel (Night, 1960) briefly mentioned the Allied bombing raids in and around the Auschwitz complex.

Several documents concerning the British rejection of requests to bomb Auschwitz surfaced during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, setting off a flurry of discussions about the issue in the British press during 1961 and 1962, as well as a brief airing in parliament. Assistant Secretary McCloy’s aforementioned letter rejecting bombing and speculating about “more vindictive action” also made its first postwar public appearance at that time, in the pages of the New York Herald Tribune.

Also in 1961, Rabbi Weissmandl’s aforementioned appeal for bombing was reprinted in Ben Hecht’s book Perfidy, a sharp attack on the Zionist leadership’s response to the Holocaust. The first major scholarly history of the Holocaust, Raul Hilberg’s The Destruction of the European Jews (1961), briefly mentioned Chaim Weizmann’s appeals to the British to bomb Auschwitz.

As books and essays dealing specifically with the Allies’ response to the Holocaust began appearing in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the bombing question began to attract more public attention. These included brief references in While Six Million Died, by Arthur Morse (1968), The Politics of Rescue, by Henry Feingold (1970), and No Haven for the Oppressed, by Saul Friedman (1973), as well as essays in journals such as Patterns of Prejudice, American Jewish Historical Quarterly, and Judaism.

The visit by U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance to Yad Vashem in 1977 stirred some discussion of the topic, when officials of Yad Vashem told the news media that Vance “showed particular interest” in a reproduction of one of the John McCloy letters. Vance reportedly remarked, “Even my country didn’t act.”

The turning point in public awareness of the bombing issue was the publication, in Commentary magazine in 1978, of Prof. David S. Wyman’s essay, “Why Auschwitz Was Not Bombed.” Wyman exposed the real reason for the War Department’s refusal to seriously consider bombing Auschwitz, that is, its predetermined policy to refrain from aiding humanitarian objectives. He also showed that both American and British planes had sufficient range to strike Auschwitz and return to their bases.

In addition, Wyman’s essay revealed the scope of American and British bombing of German targets in and around Auschwitz, including some less than five miles from the gas chambers, thus shattering the “diversion” argument that had been put forth in 1944 by the War Department.

Wyman also identified a number of the Jewish leaders and organizations who called for bombing the camp: Isaac Sternbuch, a leading Orthodox rescue activist in Switzerland; Slovak Jewish activists Gisi Fleischmann and Rabbi Michael Weissmandel; Gerhart Riegner, of the World Jewish Congress in Geneva; the Bergson Group’s Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe; the Va’ad Ha-Hatzala rescue committee in New York City; Ernest Frischer of the Czech government in exile; British Jewish groups (representatives of the Board of Deputies of British Jews and the London office of the World Jewish Congress); and Yitzhak Gruenbaum of the Jewish Agency. He also noted that A. Leon Kubowitzki of the World Jewish Congress opposed bombing from the air.

The following year, Bernard Wasserstein, in Britain and the Jews of Europe 1939-1945, documented the unsuccessful attempts by Jewish leaders to convince the Churchill administration to bomb Auschwitz. In addition to providing new details about the lobbying undertaken by Weizmann and Shertok in London, Wasserstein for the first time named a number additional proponents of bombing: the Jewish Agency’s representatives in Geneva (Lichtheim), Budapest (Krausz) and London (Linton), and A.G. Brotman of the Board of Deputies of British Jews.

Martin Gilbert’s Auschwitz and the Allies (1981) added several more: Nahum Goldmann, the Washington, D.C. representative of the Jewish Agency and cochair of the World Jewish Congress; Chaim Pozner, of the Agency’s Geneva office; and Benjamin Akzin, Revisionist Zionist activist and War Refugee Board staff member. Monty N. Penkower’s The Jews Were Expendable (1983) lengthened the list of bombing advocates to include Ignacy Schwartzbart, of the World Jewish Congress (and Polish National Council), and Reuben Hecht, the Bergson Group’s representative in Switzerland.

The last major outstanding question was the position of David Ben- Gurion and the Jewish Agency Executive. Prof. Dina Porat of Tel Aviv University, in her 1990 book, The Blue and the Yellow Stars of David, described the June 11, 1944 meeting of the JAE and quoted from its minutes, noting that the initial opposition of Ben-Gurion and others was based on their ignorance of the true nature of Auschwitz.

The information that JAE members had received about Auschwitz at that point was fragmentary and inconclusive, in part “because none of it came from someone who had actually been there.” Until June, “the real nature of Auschwitz…was not understood in Palestine or anywhere else.” The arrival of the Vrba-Wetzler report, in late June, was “the turning point,” Porat wrote. “In the wake of this new information,” she concluded, “the JAE reversed its decision” and Agency officials around the world began lobbying for bombing. Among them, she noted, was Eliahu Epstein, who lobbied a Soviet diplomat in Cairo.

Shabtai Teveth, of Tel Aviv University, in his 1996 book Ben-Gurion and the Holocaust, agreed with Porat on this point, as did the other major study of Palestine Jewry’s response to the Holocaust, Arrows in the Dark: David Ben-Gurion, the Yishuv Leadership, and Rescue Attempts during the Holocaust, by Tuvia Friling of Ben-Gurion University, was published in English in 2005.

As a result of the fall of the Soviet Union, new documents on the subject became accessible. In early 2000, the Israeli and Russian governments jointly published a two-volume collection of documents from their respect archives pertaining to relations between the USSR and the Zionist movement. It included a report to Ben-Gurion by Jewish Agency official Eliahu Epstein about his attempt to persuade a Soviet diplomat in Cairo that the Soviets should bomb Auschwitz.

The documents resolving the question of the Jewish Agency’s reversal were discovered by Rafael Medoff in the newly-reopened Yitzhak Gruenbaum collection at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem, and published in a 2009 monograph by the David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies.

Sources: Wyman, The Abandonment of the Jews, pp.288-307;

Medoff, FDR and the Holocaust, pp.165-192.