The response of America’s churches and other Christian religious institutions to the persecution of European Jews in the 1930s and 1940s was generally weak.

Most American Christian leaders strongly condemned the November 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom, but few advocated practical steps to help the Jews. The liberal U.S. Catholic publication ‘Commonweal’ called for suspending America’s immigration quotas in order to admit more refugees.

The larger Catholic weekly magazine ‘America,’ however, took a different line. ‘America’ headlined its post-Kristallnacht issue “NAZI CRISIS.” The two feature stories did not focus on the plight of Hitler’s Jewish victims, however; one was about the mistreatment of nuns by Nazis in Austria, while the other charged that protests by American Jews against the Nazi pogrom were generating “a fit of national hysteria” intended “to prepare us for war with Germany.”

An editorial titled “The Refugees and Ourselves” focused on the “grave duty” of American Catholics to help European Catholic refugees. Jewish refugees were not even mentioned.

A post-Kristallnacht editorial in the leading U.S. Protestant magazine, Christian Century, argued that America’s own economic problems necessitated “that instead of inviting further complications by relaxing our immigration laws, these laws be maintained or even further tightened.” Christian Century also opposed the Wagner-Rogers bill to admit 20,000 refugee children; it argued that “admitting Jewish immigrants would only exacerbate America’s Jewish problem.”

In the wake of the Allied confirmation of the Nazi genocide in December 1942, leaders of the Federal Council of Churches, the national umbrella organization for 25 American Protestant denominations, pledged to the Synagogue Council of America that it would cooperate with Jewish organizations in mobilizing Christian involvement in protests. However, the only major Holocaust-related project on which the FCC collaborated, the Day of Compassion, did not materialize until nearly five months later.

Despite the fact that the Federal Council provided church leaders with a packet of materials to guide the proposed memorial services, and undertook a mailing to 70,000 Protestant ministers of an issue of the FCC Information Service newsletter devoted entirely to the mass murder of the Jews, relatively few churches participated in Day of Compassion events.

In a few communities, such as Chattanooga, Norwalk, Denver, and Raleigh, local Christian clergymen made guest speeches at Jewish community gatherings. Churches held their own prayer services for European Jewry in some other cities, such as Indianapolis, Detroit, St. Paul, Milwaukee, and a number of towns in New York, Alabama, and Pennsylvania.

In larger cities, however, participation was disappointing. In Boston, only eight local clergymen organized memorial services despite a heavy publicity campaign, including mailings, subway posters, newspaper ads, and a sponsoring committee of governors, mayors, and congress members. Likewise, in New York City, there were only a few participating clergy. In Pittsburgh, a Jewish organization hoping to prepare an article for the local press about the Day of Compassion events could not find a single church that intended to take part. Overall, only a small handful of America’s many thousands of churches sponsored special services or otherwise took part in the memorial activities.

As for American Catholics, the Catholic Committee for Refugees (est. 1937) helped only a small number of people (many of them not Jews) and the financial support it received from the church was so meager that the CCR had to be funded in part by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. The two U.S. Catholic relief agencies, the Bureau of Immigration and the War Relief Services, focused their attention entirely on Catholic refugees. Even after the Allies’ confirmation of the mass murder of Europe’s, the National Catholic Welfare Conference, representing the national Catholic bishops, did not issue a single statement concerning the genocide.

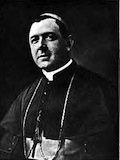

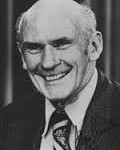

A small number of prominent individual clergymen were associated in some capacity with the Bergson Group’s campaign for U.S. rescue action. For example, the Catholic archbishop of Los Angeles, Most Rev. John Cantwell, and Episcopal bishop of Los Angeles, Rt. Rev. W. Bertrand Stevens, co-chaired the Hollywood Bowl performance of “We Will Never Die.” The list of cosponsors of the group’s 1943 emergency conference on rescue included the Episcopal bishops of Los Angeles, Lexington, and Iowa, as well as General Theological Seminary president Howard Chandler Robbins and Guy Emery Shipler, editor of The Churchman. The Methodist bishop of Virginia, James Cannon, Jr., was a speaker at that conference, as was the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, Henry St. George Tucker, who defied a personal plea by Rabbi Stephen Wise to cancel his association with the Bergsonites. A number of clergymen also signed Bergson Group newspaper advertisements or publicly endorsed its congressional resolution on rescue. The Methodist Resident Bishop, William J. McConnell, testified before Congress in support of the resolution.

Sources: Wyman, The Abandonment of the Jews, pp.317-320;

Medoff and Golinkin, The Student Struggle Against the Holocaust, pp.76-80.