In 1931, two years before the Nazis rose to power, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) awarded the 1936 Olympic games to Germany. After Adolf Hitler became chancellor in 1933, anti-Nazi activists in the United States began arguing that Nazi Germany’s policies should disqualify Berlin from hosting the games. They pointed out that the exclusion of Jews from German athletic organizations and denying Jews access to government-funded training facilities contravened the IOC’s requirements of equal treatment for all competitors.

To counter such criticism, the Nazis permitted fencer Helene Mayer, who was of partial Jewish descent but did not consider herself Jewish, to return from exile and serve on the German Olympic team. Ironically, Mayer had fled Germany in 1933 because of the regime’s discrimination against those who were categorized as “Mischling,” that is, “mixed race.” Mayer ended up winning a silver medal at the Berlin games. On the winners’ stand, she wore a swastika armband and gave the Hitler salute.

Hitler also invited a German Jewish high jumper, Margaret Lambert, to take part in the try-outs. That gave ammunition to supporters of U.S. participation, such as American Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage. Visiting Germany to inspect preparations for the games, he claimed that Jewish athletes were being allowed to train adequately in separate, privately-funded facilities.

Lambert’s try-out jump of 1.60 meters tied the German high-jump record, but just days before the games opened, she was informed by the authorities that she did not make the team because of her “mediocre performance.” The Germans did not even have three women high jumpers to field, as did other Olympic teams. One of their two jumpers later turned out to be a man who disguised himself as a woman on orders from Nazi officials. Ironically, the Hungarian athlete who won the high-jump in the 1936 games reached the same height Lambert did in the try-outs, 1.60.

THEY REFUSED TO GO

During the months preceding the 1936 games, many prominent Americans called for boycotting the Oympics to protest the Nazis’ persecution of German Jewry. The July 1935 pogrom against Jews in Berlin, and the promulgation of the anti-Jewish Nuremberg Laws two months later, increased U.S. public opposition to the games. In addition to American Jewish organizations, groups such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Catholic War Veterans also endorsed the boycott.

A number of American Jewish athletes refused to go to Berlin, including championship jumper Syd Koff, who had won four gold medals at the 1932 Maccabean Games in Tel Aviv and had qualified for the 1936 team. Star sprinter Herman Neugass of Tulane University wrote to a New Orleans newspaper: “It’s my unequivocal opinion nobody should go because of the way Jews are treated.” Harvard track and field stars Norman Cahners and Milton Green also boycott the games, as did speed skater Jack Shea, a Catholic, who had won a gold medal in the 1932 games, also boycotted the games.

The Long Island University Blackbirds basketball team was widely regarded as the top team in the country. Its players –some of whom were Jewish and some not– voted unanimously to boycott the Olympics to protest the Nazis’ persecution of German Jews. Their action stunned the sports world. One prominent sports columnist, Frank Eck, chastised the Blackbirds for causing “ill feelings” by bringing the German Jewish issue into the discussion.

The Amateur Athletic Union, which certified American athletes to compete in the Olympics, debated the issue at its December 1935 convention. It resolved –by just two and a half votes– to endorse America’s participation.

NAZI “HOSPITALITY”

Shortly before foreign visitors began arriving in the summer of 1936, antisemitic literature was taken off the newsstands in Berlin. Physical assaults on Jews were kept to a minimum during the games. Visiting journalists were impressed. The New York Times praised the German government for its “flawless hospitality.” A Los Angeles Times correspondent wrote: “Zeus, in his golden days, never witnessed a show as grand as this.” An editorial in that newspaper even predicted that the “spirit of the Olympiads” would “save the world from another purge of blood.”

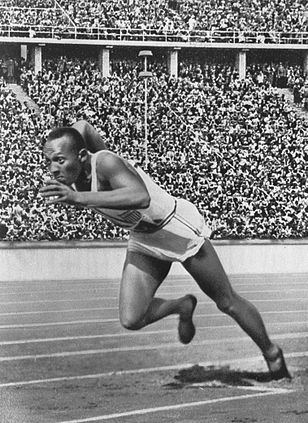

Many Americans derived satisfaction from the fact that an African-American track star, Jesse Owens, won four gold medals in the Berlin games. Some observers believed Owens’s success undermined Hitler’s claims of Aryan racial superiority. Two of Owens’s Jewish teammates, Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller, were removed from the competition at the last minute; the coaches feared the Nazis would be offended if Jewish athletes took part.

The Berlin Olympics gave Hitler a way to soften his public image and allay the international community’s concerns about his bigotry, violence, and militarism. Even President Roosevelt was taken in, at least to some extent. He told American Jewish leaders how he impressed he was to learn from two tourists who attended the games “that the synagogues are crowded and apparently there is nothing very wrong in the situation [of Germany’s Jews] at present.”

Sources: Lipstadt, Beyond Belief, pp.74-83;

Medoff, FDR and the Holocaust, p.85.