Shortly after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the leader of Revisionist Zionism, asked the British to create a Jewish armed force to take part in the war against Hitler. Twenty-five years earlier, Jabotinsky had successfully lobbied London to create the Jewish Legion, which helped the British liberate Palestine from Turkey. The Revisionist leader hoped that a new Jewish army would strengthen Jewry’s postwar case for statehood, and provide the nucleus of the army of the Jewish state-to-be. The British initially rebuffed the proposal, worried that the creation of a Jewish army would anger Arab opinion: “A Jewish Army cannot be dissociated from Jewish Nationalism,” one Foreign Office official complained to a colleague. “A Jewish nation supported by a Jewish Army under its own banner is only one step removed from the full realization of political Zionism.”

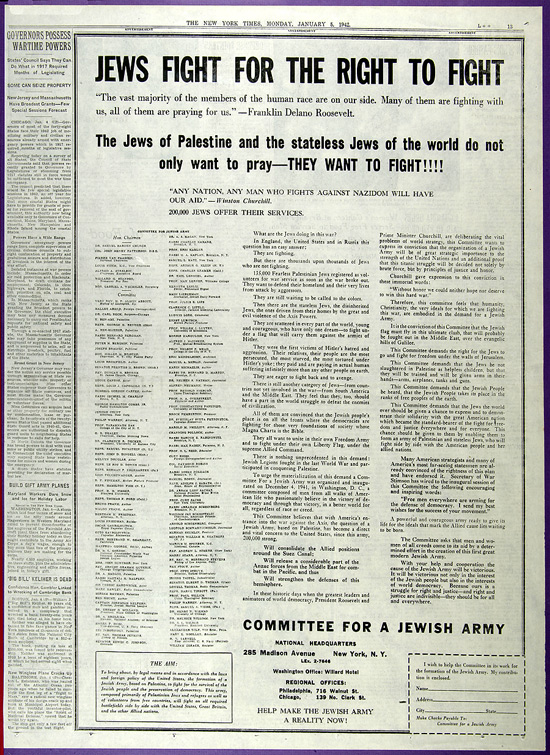

Jabotinsky then turned his attention to Washington. Arriving in the United States in early 1940, the Revisionist leader launched a campaign to win U.S. support for the Jewish army idea. After Jabotinsky’s death later that year, the Jewish army campaign was spearheaded by two of his followers, Hillel Kook (using the pseudonym “Peter Bergson”) and Benzion Netanyahu. Their “Committee for a Jewish Army of Stateless and Palestinian Jews” sponsored full page newspaper advertisements, lobbied on Capitol Hill, and mobilized a coalition of supporters that included members of Congress from both parties, Hollywood celebrities, African-American leaders, and prominent artists, writers, and musicians. The committee was also active in Great Britain, where its chapter was led by Irgun emissary Jeremiah Halpern and strongly supported in parliament by Lord Straboli.

The State Department feared that, as one official put it, the “agitation for the formation of a Jewish army” was having an “alarming effect” by arousing anti-American feeling in the Arab world. American Zionist efforts on behalf of a Jewish army and Jewish statehood were the main impetus for the proposal by the State Department and the British Foreign Office to issue a joint Anglo-American statement in 1943 banning all public of the Palestine issue until war’s end.

Despite the opposition of the American and British governments, the Jewish army activists eventually triumphed, albeit on a smaller scale than they hoped. A combination of public activism by the Jabotinskyites and behind-the-scenes diplomacy by mainstream Zionist leaders finally convinced the British that creating a Jewish fighting force was necessary to impress American public opinion. Churchill explained his 1944 decision to create the Jewish Brigade in these terms: “I like the idea of the Jews trying to get at the murderers of their fellow-countrymen in Europe, and I think it would give a great deal of satisfaction in the United States.”

Because it was established so late in the war, the Jewish Brigade fulfilled only a part of its supporters’ hopes. It saw only limited action on the battlefield and did not undertake the retaliatory raids its proponents hoped might deter Nazi masacres of Jewish civilians. However,, Brigade veterans did play an important role in the postwar smuggling of Holocaust survivors to Palestine, and later used their military experience to help fend off the Arab armies which invaded the newborn State of Israel in 1948.

Sources: Penkower, The Jews Were Expendable, pp.3-29;

Baumel, The Bergson Boys, pp.101-112;

Wyman and Medoff, A Race Against Death, pp.20-28.