Dutch playwright Jan de Hartog (1914-2002) used the voyage of the refugee ship St. Louis to inspire some of his countrymen to hide Jewish children from the Nazis.

The son of a Dutch Calvinist Minister, de Hartog always exhibited a love for the sea, and even ran away at age 11 to become a cabin boy on a Dutch fishing trawler. In early 1940, de Hartog produced and starred in a film about the Dutch navy, “Somewhere in Holland.” At almost the same time, his first novel appeared: Holland’s Glory, which depicted the life of Dutch sailors in striking and glamorous terms, was published just days before the German invasion of Holland in May 1940. The novel sold more than a half-million copies and de Hartog became a living symbol of Dutch national pride.

The German occupation authorities regarded de Hartog as a threat. They banned the book and the film on the grounds that they were arousing “national passions,” and de Hartog went into hiding to avoid arrest. At one point, he lived in an old age home, disguised as an elderly woman. “The Dutch film studios were closed, and everybody connected with them was thereby officially unemployed and liable to be deported to Germany as slave labor,” de Hartog recalled many years later, in a talk at Weber State College, in Maine. “We decided to go underground and form the ‘Underground Theatre,’ which would travel through the country and perform in barns and haylofts and, in the case of the Zuider Zee [the famous Dutch bay], in those large sheds where the fishermen dried and mended their nets. As we thought it was too dangerous for women, we decided it would have to be a play for men only. Of course that was a silly conclusion, as it turned out, the women were much better at underground activity than the men, but that’s another chapter.”

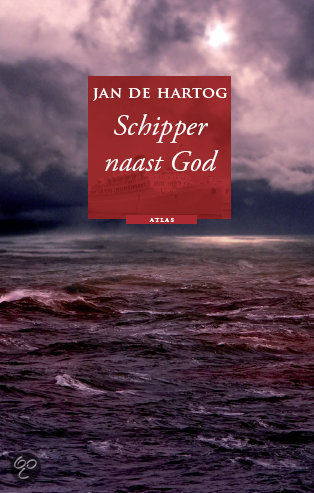

The voyage of the St. Louis was well known in Holland; the government had granted temporary haven to 181 of the passengers. In the summer of 1942, as the Germans began preparations for the mass deportation of Dutch Jews to Auschwitz, de Hartog wrote “Schipper Naast God,” or “Skipper Next to God,” a play based on the St. Louis tragedy, although with a different ending. In de Hartog’s play, a German ship with Jewish refugees is turned away from South America, so the skipper sails it to Long Island, where he beaches the ship in the midst of a yachting competition, forcing the yachtsmen to rescue the passengers.

“We performed the play especially around the Zuider Zee, where I knew the fishermen very well,” de Hartog later explained. “They were ideal hosts for Jewish children. In those troubled times, there was a great demand for families that would accept Jewish children and hide them. The fishermen were ideal because they were a closed society, but they had a problem because they were against the Jews ‘who had crucified Christ.’ They had to be convinced that it was a long time ago, and that at this point their Christian duty was to give sanctuary to these persecuted Jews. The play was an instrument to try and bring that about. We were successful; a number of children were placed with the fishermen. After each performance, the audience and players entered into lively discussions which were really the main part of the whole performance.”

The size of the cast, however, became a problem: with seventeen actors, the performances might attract the Germans’ attention. “So I learned the play by heart and reached the ideal of every playwright: I sat down in front of an audience and acted out all the parts myself,” de Hartog later explained. “I recited the whole play with appropriate facial expressions, looking this way and that, to make sure that everyone understood that it was a different character. I had a whale of a time. I did about three hundred of these performances. The manuscript had been destroyed because there were house searches, and it was decided that there should be no copy of the play available. So there I was, acting all the parts by myself.”

The exact number of children who were sheltered as a result of de Hartog’s play is not known. Altogether, an estimated 25,000-30,000 Dutch Jews were hidden with the help of the Dutch underground, and about two-thirds of them survived the Holocaust. More than 100,000 Dutch Jews were murdered in Auschwitz.

With the Gestapo closing in, de Hartog fled the Netherlands and reached England in 1943. There he assisted a group of exiled Dutch sailors who aided the war effort by undertaking hazardous missions for the British military. De Hartog gained fame as a playwright in the United States after the war. “Skipper Next to God” was performed on Broadway in 1948, directed by Lee Strasberg and starring John Garfield. In 1953, “Skipper” was made into a movie.

The New York Times, reviewing the Broadway version, was not enthusiastic about “Skipper” as a play, but argued that it “deserves to be produced” because of its “high-minded” purpose in showing that during the Holocaust years, “in America no one doubts that morally the Jews should be admitted, but everyone comfortably hides behind the letter of the law” in keeping them out.

Sources: Medoff, Revisiting the Voyage of the Damned pp. 63-64.