Author, playwright and Hollywood screenwriter Ben Hecht (1894-1964) was a leading activist for the rescue of European Jews from the Holocaust and creation of a Jewish State.

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Hecht grew up in Racine (Wisconsin) and Chicago in what he described as a “large, extended, nutty Jewish family of wild uncles and half-mad aunts.” One of his most vivid childhood memories was of his Aunt Chasha taking him to a play in which a policeman wrongly accused another character of theft. The excitable young Ben shouted in protest from the audience, prompting the theater manager to demand an apology for the child’s disruptive behavior. Chasha responded by hitting the manager over the head with her umbrella. “Remember what I tell you,” she explained to her nephew. “That’s the way to apologize.”

That attitude seems to have guided Hecht as he blazed his way through every challenge or cause he took on. His first novel landed him in court on obscenity charges; Clarence Darrow served as his defense attorney. (Hecht lost the case but won national notoriety.) Just five years later, he won the very first Academy Award for original screenplay –for “Underworld”– although the irreverent Hecht boasted that he used the Oscar statuette as a doorstop. A year after that, his play about the newspaper business, “The Front Page,” was a smash hit on Broadway.

Surveying a career that included 65 film scripts (including “Gone with the Wind”), 25 books, 20 plays, and hundreds of short stories and magazine articles, film critic Judith Crist dubbed Hecht “the most prolific multimedia child of this century.”

As a young man, Hecht had shown no real interest in his Jewish heritage. But the rise of Nazism and the persecution of Europe’s Jews transformed him. First he joined the Fight for Freedom Committee, which advocated pre-emptive U.S. military action to oust Hitler. He wrote a fundraising pageant for the group, called “Fun to Be Free,” which drew more than 17,000 people to Madison Square Garden in 1941.

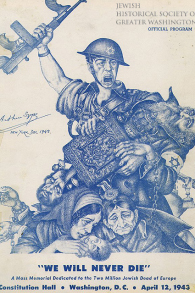

Hecht became a supporter of the Bergson Group when it was known as the Committee for a Jewish Army of Stateless and Palestinian Jews. His first project with the Bergson Group was “We Will Never Die,” a dramatic 1943 pageant to raise American public awareness of the Nazi genocide.

Starring Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni, it was staged at Madison Square Garden before audiences totaling more than 40,000, before traveling to Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, the Hollywood Bowl, and Washington D.C., where the audience included First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, six Supreme Court justices and several hundred Members of Congress.

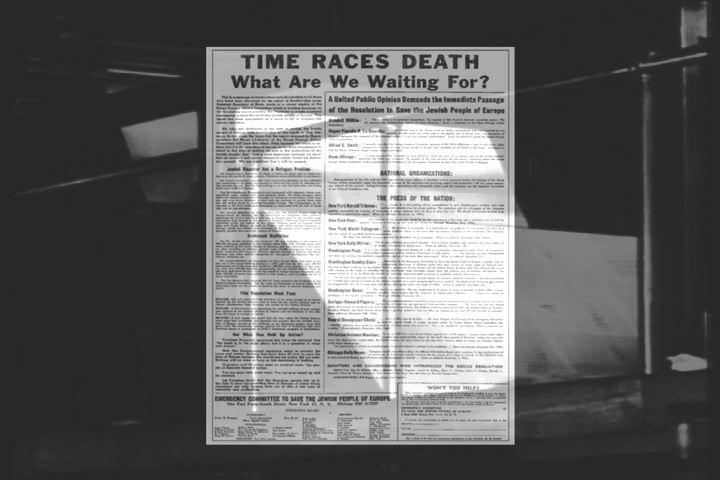

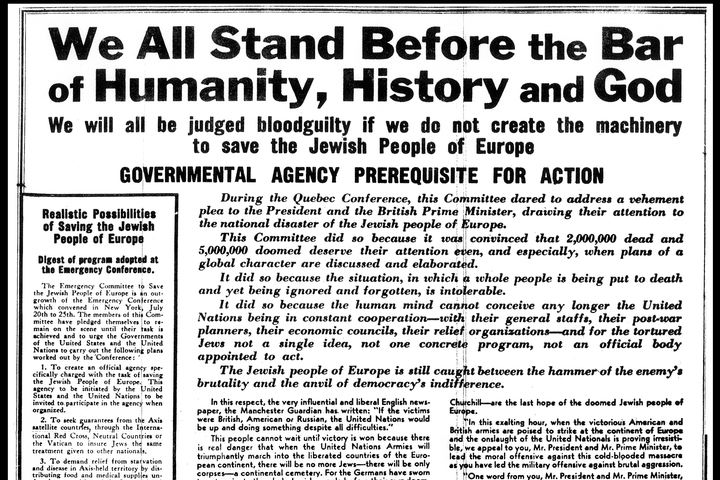

During the 1940s, the Bergson Group sponsored numerous full-page newspaper ads calling for U.S. action to rescue Jews from Hitler.

The ads, many of them authored by Hecht, featured eye-catching headlines such as “Time Races Death: What Are We Waiting For?” and “How Well Are You Sleeping? Is There Something You Could Have Done to Save Millions of Innocent People–Men, Women, and Children–from Torture and Death?”

“Our mission in the United States would not have attained the scope and intensity it did if not for Hecht’s gifted pen,” senior Bergson group activist Yitshaq Ben-Ami later wrote. “He had a compassionate heart, covered up by a short temper, a brutal frankness and an acid tongue.”

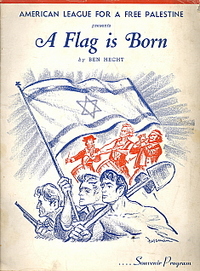

“A Flag is Born,” which the British press called “the most virulent anti-British play ever staged in the United States,” raised an estimated one million dollars, part of which was used by the Bergson Group to purchase a ship –named the S.S.Ben Hecht– to bring Holocaust survivors to Palestine in defiance of British immigration restrictions. The ship was intercepted by the British and its 600 passengers were interned in Cyprus. They reached the Holy Land only after the establishment of Israel.

A planned performance of “Flag” at the Maryland Theater, in Baltimore, ran into trouble when Hecht discovered that the theater restricted African-Americans to the balcony. A last-minute pressure campaign by an alliance of the Bergson Group and the local NAACP brought down that racial barrier–the first time that blacks were able to sit freely in a Maryland theater. Exuberant NAACP leaders hailed the “tradition-shattering victory” and used it to help pave the way for the desegregation of other Baltimore theaters.

“I am proud that it was my play which terminated one of the most disgraceful practices of our country’s history,” Hecht declared after the opening performance in Baltimore. “The incident is forceful testimony to the proposition that to fight discrimination and injustice to one group of human beings affords protection to every other group.”

Hecht’s postwar broadsides for the Bergson Group openly supported the Jewish armed revolt against British forces in Palestine. In one advertisement, he wrote: “Every time you blow up a British arsenal [in Palestine], or wreck a British jail, or send a British railroad train sky high, or rob a British bank or let go with your guns and bombs at the British betrayers and invaders of your homeland, the Jews of America make a little holiday in their hearts.”

Outraged British Embassy officials in Washington sought–unsuccessfully–to convince the Truman administration to deport Bergson, revoke the Bergson Group’s tax-exempt status, or at least prohibit government employees from publicly endorsing the group. None of those efforts succeeded. But Hecht’s writings did convince England’s Cinematograph Exhibitors Association –the distributor of films to British movie theaters– to ban all movies in which Hecht had a hand. As a result, the only way Hecht could find work was by reducing his usual screenwriting fee by half and agreeing that his name would not appear in the credits. The boycott did not end until 1952. “Long after the British had forgiven all the other Jews who had battled them–allowing even [Irgun Zvai Leumi leader] Menachem Begin to publish his memoirs in London–they continued to berate and boycott me,” Hecht later wrote, “as if, God save me, I was busy shelling the coast of Albion with some private cannon.”

Sources: Gil Troy, “From Literary Gadfly to Jewish Activist,” pp.431-449;

Medoff, Militant Zionism in America, pp.79-80, 158-160.