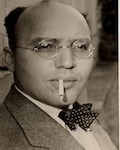

As secretary of the interior under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harold L. Ickes (1874-1952) repeatedly found himself at odds with the president over U.S. policy toward Europe’s Jews.

A draft of a speech by Ickes condemning the 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany was censored by the president himself, who insisted that he “cut out all references to Germany by name as well as references to HItler, Goebbels, and others by name,” according to Ickes’s diary.

After the governor and legislative assembly of the Virgin Islands, a U.S. territory, offered to open their doors to Jewish refugees after Kristallnacht, Secretary Ickes became an active proponent of the plan. President Roosevelt blocked the proposal, asserting in a memo to Ickes that the Virgin Islands already had its own “social and economic problem[s],” and bringing in refugees would only make matters worse. “I cannot do anything which would conceivably hurt the future of present American citizens,” FDR wrote.

Ickes supported the 1939 Wagner-Rogers bill, which would have admitted 20,000 German Jewish refugee children outside the quota system. The president, however, refrained from supporting the measure, and it was buried in a subcommittee. In 1939-1940, Ickes also supported legislation to open Alaska to Jewish refugees. President Roosevelt watered down that proposal so that only 10% of the immigrants would be Jews. Eventually the bill was buried altogether.

Ickes’ support helped Eleanor Roosevelt convince the president, in 1940, to authorize an Emergency Visas program for endangered anti-Nazi political refugees in Europe, many of them Jews. About 2,000 such refugees entered the United States in1 1940-1941.

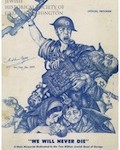

In 1943, Ickes agreed to serve as honorary co-chairman of the Washington, D.C. chapter of the Bergson Group’s Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe. That prompted a letter from Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, imploring Ickes to “withdraw from this irresponsible group” which, he claimed, “has not done a thing which may result in the saving of a single Jew.” After meeting with Bergson to review Wise’s accusations, Ickes informed Wise that he would not resign, and he urged Wise to refrain from “becoming engaged in another of those finger-pointing disputes that only weaken the great purpose” of the rescue campaign.

Sources: Wyman, Paper Walls, pp. 101-103, 112-113, 149-150;

Feingold, The Politics of Rescue, pp. 155-157.